Obituary: Yevgenii Yevtushenko

Yevgenii Aleksandrovich Yevtushenko, Russian poet (18 July 1933 – 1 April 2017)

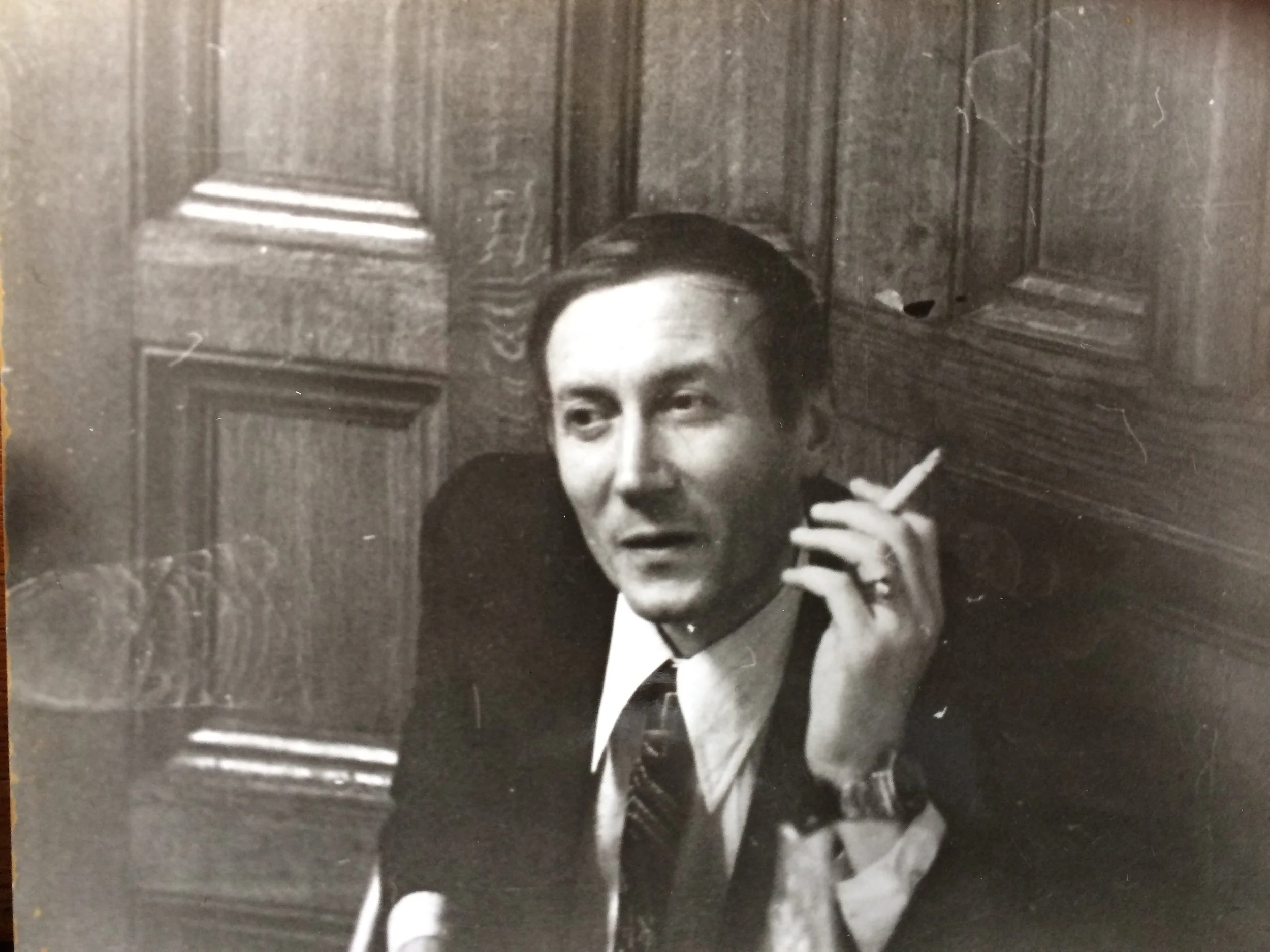

Yevtushenko in the 1970s. Image © Simon Franklin

One of the oddest documents in my desk is an un-headed, un-stamped A4 sheet, hastily typed and with scraggy handwritten corrections. Dated 14 July 1983, it is addressed to the customs officials at Sheremetevo airport. Dorogie tovarishchi (dear comrades), it begins. Today, it says, my friends from Britain arrive at 17.00. Today in the Olympic complex my 50th-birthday concert begins at 19.00. Please let my friends through vne ocheredi (without queuing), so that they won’t be late. Signed, Yevgenii Yevtushenko. So many aspects of this seem bizarre in retrospect: that anybody might seriously write such a note to customs officials; that customs officials could be expected even to recognize, let alone pay any attention to, a personal note bearing the unverified signature of a poet; that a poet would be performing at an Olympic-sized arena. Most bizarre of all: this actually worked. Only in the late Soviet era. Only Yevtushenko.

Why did all this not seem so odd at the time? Why was the mere name enough to circumvent normal border controls? Why was the huge arena packed? Yevtushenko has had many reputations. In the West he was and is most often treated as a voice of the Thaw, as the poet of Babii Yar and Nasledniki Stalina. Among post-Soviet intellectuals he was often regarded superciliously as the tame Soviet semi-dissident, serving the regime that he purported to criticize. Both attitudes are political, though often voiced by people who affect to despise the political contamination of literary values.

Neither assessment meant a great deal to the throng of his fans at the Olympic complex. They wanted the mesmeric performance, his peculiar style of declamatory lyricism that in other contexts, or from anyone else, might have seemed merely bombastic. Two poems were printed in the leaflet serving as a programme, and for me they represent Yevtushenko better than either ‘The Bratsk Hydro-Electric Station’ (Bratskaia GES) or ‘The Tanks Roll Through Prague’ (Tanki idut po Prage). I can still hear him caressing the air and his audience with the almost indecently lush assonances and alliteration of the refrain of ‘Sleep, my beloved’ (Liubimaia, spi…):

И море всем топотом, And the waves ever bustling,

И ветви – всем ропотом, And the boughs all rustling,

и всем своим опытом – And memories hustling

пёс на цепи, And the dog on its chain,

и я тебе – шепотом, I tell you, whispering,

потом полушепотом, And then half-whispering,

потом уже – молча: Then already unspeaking,

“Любимая, спи…” “Beloved one, sleep…”

The other poem – ‘White snow falling’ (Idut belye snegi) - gets more air-time now in Russia. Its form is classic elegy, in quiet stanzas of restrained two-foot anapaestic lines: nature eternal and repetitive and impervious; reflections on mortality, on his own mortality, and on remembrance; and, laced into the fabric of the poet’s persona, Russia. This becomes clear in the second half of the poem:

Идут белые снеги, White snow falling

как во все времена, As it has in all times,

как при Пушкине, Стеньке In Pushkin’s and Stenka’s,

и как после меня, As it will after mine;

Идут снеги большие, Heavy snow falling

аж до боли светлы, So bright it brings pain,

и мои, и чужие Sweeping others’ traces

заметая следы. Sweeping mine away.

Быть бессмертным не в силе, I cannot be immortal

но надежда моя: But hope is mine:

если будет Россия, If Russia survives,

значит, буду и я. Then so will I.

Yevtushenko was global in his curiosity and ambition, Soviet in his sense of the historical moment, Soviet also in the ways in which he tends to be framed; so it is almost shocking to see here the directness of his declaration of an essential Russianness as the core of his identity and aspiration.

In an age when almost nobody from the Soviet Union travelled, Yevtushenko travelled everywhere, knew everybody. He reckoned he had visited over seventy countries. He was translated into over eighty languages. He met Kennedy, Castro, Neruda. He was perhaps unworthily proud of all of that. But he also had the gift of generous attentiveness, no matter who he was with. Talking with people about their recollections of Yevtushenko, I have been struck by how vivid, and how generally warm, are their memories even of the briefest of encounters. Among his memorable qualities was physical energy, his constantly mobile face, his restless mind. His creative output astonished in quantity and diversity. His poetry ranged from intimate lyrics to grand quasi-epic cycles. He was a novelist, film actor, film director, a published photographer. He was also an anthologist on the grand scale, constantly revising and enlarging ever more vast collections of Russian poetry. He probably wrote far too much, or at any rate published far too much; weak Yevtushenko pieces are easy to find. He became easy prey for parodists. Sneering remains easy; but he was an extraordinary talent nonetheless.

After a brief infatuation with elective politics in the Gorbachev Spring, Yevtushenko soon discovered the hard lesson that so often brings disillusionment for (and in) intellectuals: to speak to power is one thing; to have it – quite another. He spent most of his last 25 years quietly, by his standards, based in Tulsa, where, by all accounts, he was a popular and conscientious lecturer, and where, on 1 April, he died. In his final few years he enjoyed fresh popularity in Russia, with readings, books, interviews, tours. He was the only one left, the only link to that age of what now looks like naïve optimism; a curiosity; a dinosaur; a national treasure.

One of Yevtushenko’s best known aphoristic lines was ‘A poet in Russia is more than a poet’ (Поэт в России – больше, чем поэт). Not any more. For better, for worse, he was the last.

Professor Simon Franklin (University of Cambridge)

Translations of ‘Sleep, my beloved’ and ‘White snow falling’

© BASEES Newsletter editorial team