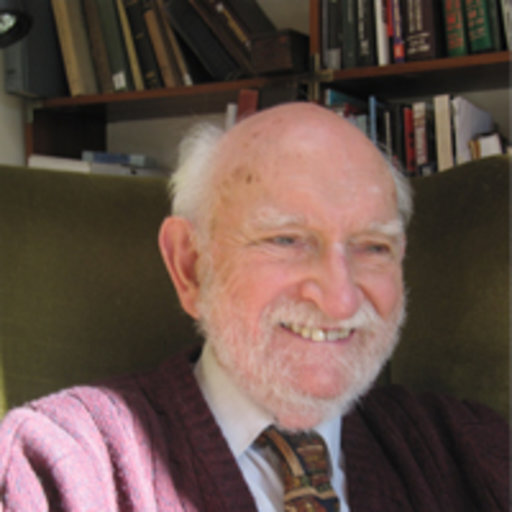

Robert William Davies, 1925-2021

Robert William (“Bob”) Davies, who died on 13 April 2021, was born in London on 23 April 1925. After war service in the RAF, he graduated in 1950 from the School of Slavonic and East European Studies, London. Under the guidance of Alexander Baykov at the University of Birmingham, he investigated Soviet public finance, obtaining his PhD in 1954 (Davies 1958). After two years lecturing at Glasgow, he returned to Birmingham in 1956, remaining there until his retirement in 1988. He was the founding director of Birmingham’s Centre for Russian and East European Studies from 1963 to 1979, being promoted to Professor of Russian Economic Studies in 1965. He was a keen supporter of BASEES and its predecessor NASEES, serving on the NASEES committee and taking part in annual conferences.

Davies’s first work on the Soviet budgetary system already showed a strong historical interest. He was drawn further into Soviet history by the historian E. H. Carr, who was writing a multi-volume History of Soviet Russia. Carr invited Davies to join him. The result was a pathbreaking investigation of the origins of the Soviet planning system (Carr and Davies 1967). When Carr stopped his own history at the end of the 1920s, Davies continued with a seven-volume series on the Soviet economy in the decade of the 1930s, through the collectivization of agriculture, forced industrialisation, famine, purges, and war preparations (Davies 1980-2018). This work was recognized by the Alexander Nove Award for Distinguished Scholarship of BASEES in 2020. In fact, Davies’s extraordinary scholarship was admired around the world, including in Russia, the country to the study of which he devoted his life.

While engaged in this work, Davies also led a major project that surveyed Soviet industrial technology and benchmarked its achievements and shortfalls against the technologies of the West (Davies and Zaleski 1969; Amann, Cooper, and Davies 1977). He edited major documentary collections (Wheatcroft and Davies 1985; Davies et al. 2003). He wrote and edited several textbooks, including the first on Soviet quantitative economic history (Davies and Shaw 1978; Davies, Harrison, and Wheatcroft 1994; Davies 1998). He contributed major studies of Soviet and Russian historiography as it changed with the dismantling and collapse of Soviet orthodoxy (Davies 1989, 1997).

Among the most important findings of Davies’s work is that, while the ideas of Lenin and Stalin mattered a great deal, they did not predetermine the eventual shape of the Soviet economic system. The first two decades of Bolshevik rule saw a process of experimentation and adaptation, alternately spurred by radicalism and restrained by pragmatism. Like Carr before him, Davies believed that Soviet industrialisation was the most important event of the twentieth century, because it decided the outcome of World War II. His research also exposed the great social and

economic costs of forced-march economic development. It also showed that many outcomes of Soviet rule were unintended, and that Stalin’s refusal to acknowledge or adapt to the unintended outcomes greatly increased the costs of his policies, sometimes measured in millions of lives. Davies, Harrison, Khlevniuk, and Wheatcroft (2018) provide a thematic overview for students and those responsible for their reading lists.

Davies was not only an extraordinary scholar. He was also a builder and a leader. On foundations laid by Alexander Baykov, he developed the Centre for Russian and East European Studies at Birmingham into a world-leading institution. Of particular importance were the varied links that he promoted with Soviet historians despite the political and diplomatic tensions of the Cold War. At the Centre he held large ESRC research grants continuously for forty years. These supported numerous PhD students and research assistants who, having cut their teeth under his guidance, went on to lectureships and chairs of Russian studies around the world. The grants also funded a seminar series that became the core of a convivial network, joined by young and old researchers from many institutions and disciplines. Their gatherings often spilled over into the home that he shared with his wife Frances (who predeceased him), and their children Maurice and Cathy.

As a scholar, Davies was cooperative and egalitarian. He was a careful and respectful listener. He shared his prodigious knowledge freely. He nurtured enthusiasm, while reminding those who looked to him for guidance that these were not enough: scholarship also required ceaseless attention to detail, deep knowledge of sources, and the willingness to rethink cherished ideas when the evidence pointed elsewhere.

As a young adult, Davies was among those on the British left who joined the Communist Party in the 1930s and 1940s because of the Soviet Union’s stand against fascism in Germany and Italy. He left the party in 1956 after the Soviet Army’s suppression of the Hungarian uprising. Concluding the final volume (published in 2018) of his Industrialisation of Soviet Russia, he wrote of the first volume (1980):

In this book I already assumed that what had been emerging in the Soviet Union was a new civilisation . . . But the Soviet system which emerged by 1940 was fundamentally different from the new civilisation which I had envisaged when I began this work. I continued to hold my original conception when I was writing about the early 1930s. But as my work continued, and my knowledge of the later 1930s became more detailed and more reliable, it became clear that the Soviet system, despite playing a major role in the defeat of Nazism, was no longer any kind of ‘new civilisation’ or socialist society, but a repressive regime in which violence and tyranny played a major part. My earlier conception of the course of Soviet history was fundamentally mistaken.

While my view of Soviet history has changed, two things have remained the same. One constant factor in my work has been the idea that, when the details of history are in conflict with preconceived ideas, the latter should give way. Another is that I remain on the Left, believing today as before that a better organization of society is possible.

Davies is survived by his children Maurice and Cathy, daughter-in-law Nicky, and grandchildren Michael and Lucia, all of whom contributed to his care and comfort in his last years.

Mark Harrison (University of Warwick)

Selected major works (in order of publication)

Davies, R. W. 1958. The Development of the Soviet Budgetary System. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Carr, E. H., and R. W. Davies. 1967. Foundations of a Planned Economy, 1926-1929 (2 vols). Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Davies, R. W., and Eugene Zaleski (eds). 1969. Science Policy in the USSR. Paris: OECD,.

Amann, Ronald, Julian Cooper, and R. W. Davies (eds). 1977. The Technological Level of Soviet Industry. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Davies, R. W., and Denis J. B. Shaw (eds). 1978. The Soviet Union. London: Allen & Unwin.

Davies, R. W. 1980-2018. The Industrialisation of Soviet Russia. Vol. 1, The socialist offensive: the collectivisation of Soviet agriculture, 1929–1930; vol. 2, The Soviet collective farm, 1929–1930; vol. 3, The Soviet economy in turmoil, 1929–1930; vol. 4, Crisis and progress in the Soviet economy, 1931–1933; vol. 5 (with Stephen G. Wheatcroft), The years of hunger: Soviet agriculture, 1931–1933; vol. 6 (with Oleg Khlevniuk and Stephen G. Wheatcroft), The years of progress: the Soviet economy, 1934–1936; vol. 7 (with Mark Harrison, Oleg Khlevniuk and Stephen G. Wheatcroft), The Soviet economy and the approach of war, 1937–1939. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Wheatcroft, S. G., and R. W. Davies (eds). 1985. Materials for a Balance of the Soviet National Economy, 1928–1930. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Davies, R. W. 1989. Soviet History in the Gorbachev Revolution. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Davies, R. W., Mark Harrison, and S. G. Wheatcroft (eds). 1994. The Economic Transformation of the Soviet Union, 1913–1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Davies, R. W. 1997. Soviet History in the Yeltsin Era. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Davies, R. W. 1998. Soviet Economic Development from Lenin to Khrushchev. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Davies, R. W., Oleg V. Khlevniuk, E. A. Rees, Liudmila P. Kosheleva, and Larisa A. Rogovaya (eds). 2003. The Stalin-Kaganovich Correspondence, 1931–36. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Davies, R. W., Mark Harrison, Oleg Khlevniuk, and Stephen G. Wheatcroft. 2018. “The Soviet economy: the late 1930s in historical perspective.” University of Warwick, CAGE Working Paper no. 363. Download